Fitness & Ergonomics: Posture Mistakes You’re Probably Making at Work

- August 6, 2025

- 1 Like

- 216 Views

- 0 Comments

Abstract

This report synthesizes extensive secondary research on the pervasive issue of poor workplace posture and its profound implications for individual health, organizational productivity, and economic well-being. It highlights the alarming prevalence of musculoskeletal discomfort among office workers and mobile device users, detailing the cascade of physical and mental health consequences, from chronic pain and spinal degeneration to reduced cognitive function and depression. The report identifies common posture mistakes, provides comprehensive, evidence-based ergonomic guidelines for workstation setup, and emphasizes the critical role of dynamic habits and holistic personal fitness. Furthermore, it presents a compelling business case for ergonomic interventions, quantifying the significant economic burden of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) and demonstrating the substantial returns on investment through enhanced productivity, improved employee well-being, and reduced healthcare costs. By integrating expert recommendations and addressing implementation challenges, this report serves as a practical guide for individuals and organizations committed to fostering healthier, more productive work environments.

Keywords: Mobile phone, Tablet, Gadget, Laptop, Posture, Musculoskeletal symptoms, sitting positions, occupations, ergonomics, postural, low back pain, workstation, productivity, well-being, economic burden, intervention, secondary research.

Article Type: Secondary Research

1. Introduction: The Silent Epidemic of Poor Workplace Posture

1.1. The Modern Work Landscape and Postural Challenges

The contemporary professional landscape has undergone a profound transformation, largely driven by technological advancements and evolving work models. The global proliferation of mobile devices stands as a testament to this shift, with an estimated 4.77 billion mobile phone users in 2017, a figure that was predicted to rise to 5 billion by 2019.1 This widespread adoption, exemplified by a 67% penetration rate in Indonesia in 2018, has fundamentally reshaped daily activities, extending beyond communication to encompass e-commerce and teleconferencing.1 The recent global shift to remote work, such as the University of Indonesia’s Work From Home (WFH) program during the COVID-19 pandemic, further amplified the reliance on smartphones, tablets, and laptops for extended periods.1

Concurrent with the ubiquity of personal devices, there has been a significant increase in sedentary occupations. Office workers, on average, spend approximately two-thirds of their daily work time in a sitting position, frequently for continuous periods of 30 minutes or more.2 This dual trend—prolonged digital device use and extended sedentary work—has directly contributed to a simultaneous surge in musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) affecting various body regions, including the back, legs, and wrists, largely triggered by poor posture.1 The extensive adoption of mobile devices and the rise of sedentary work are not merely contributing factors but fundamental drivers of a growing musculoskeletal health crisis. This implies that traditional ergonomic solutions, often focused solely on fixed workstations, are insufficient; interventions must now adapt to address the pervasive nature of mobile device usage and flexible work environments.

1.2. Why Workplace Posture is a Critical Health and Productivity Concern

The implications of poor posture and inadequate workplace ergonomics extend significantly beyond superficial discomfort, profoundly compromising spinal health. Proper spinal alignment is paramount for distributing weight evenly across the body and preventing undue stress on the vertebrae, intervertebral discs, and surrounding tissues.3 However, work-related activities frequently necessitate prolonged periods of sitting or repetitive movements, which invariably place considerable strain on the spine and its supporting musculature.3 Prolonged sitting and static postures not only exacerbate existing musculoskeletal problems, such as low back pain (LBP) and neck pain, but are also demonstrably associated with broader systemic health consequences, including metabolic and cardiovascular issues, ultimately diminishing an individual’s overall quality of life.2

The prevalence of musculoskeletal discomfort among the working population is alarmingly high. Studies indicate that 70.5% of mobile device users report experiencing musculoskeletal symptoms, with particular concentrations in the neck (86.4%), lower back (75.9%), and shoulders (76.2%).1 Low back pain alone represents a significant public health burden, affecting between 18% and 68% of office workers annually, with a concerning chronicization rate of approximately 27% over a one-year period.2 A significant barrier to effectively addressing these pervasive musculoskeletal problems is often a fundamental lack of knowledge and alertness among workers regarding the ergonomic risks in their immediate surroundings.4 This suggests that even when effective solutions are available, a critical gap in awareness can prevent effective self-correction and proactive engagement. Consequently, simply providing ergonomic equipment or guidelines may be insufficient; a robust educational component is essential to not only inform but also cultivate a sense of personal responsibility and vigilance concerning ergonomic risks. Without this foundational understanding, even perfectly designed workspaces may be misused or underutilized, perpetuating the cycle of discomfort and injury.

2. The Hidden Costs of Bad Posture: Beyond Aches and Pains

2.1. The Spectrum of Physical Pain and Musculoskeletal Disorders

Poor posture stands as a primary contributor to the chronic back, neck, and shoulder pain experienced by millions globally.5 Specific anatomical regions frequently afflicted include the neck, reported by 86.4% of mobile device users, the lower back (75.9%), and both the right and left shoulders (76.2%).1 The biomechanical consequences of prolonged poor posture are significant: it induces imbalances within the body, causing certain muscle groups to become stretched and weakened while others become shortened and tight.5 This muscular asymmetry leads to chronic fatigue and gradual wear on the body’s structures, as muscles and tendons are forced to operate inefficiently, expending increased energy merely to maintain an upright position.5

Common musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) directly linked to sustained poor posture include low back pain, with an annual prevalence ranging from 18% to 68% in office workers, neck pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, tendinitis, and general neck strain.2 Beyond generalized pain, inadequate posture can precipitate more specific and severe conditions, such as herniated discs, sciatica, kyphosis (an excessive rounding of the upper back), and sacroiliac joint (SI joint) dysfunction.3 The extensive data reveals that the impact of poor posture extends far beyond localized pain, creating a cascade of interconnected physical and mental health issues. This demonstrates that addressing ergonomics is not merely a physical health initiative but a crucial component of comprehensive employee well-being and mental health support.

2.2. Broader Physiological Impacts

The systemic consequences of poor posture extend well beyond the musculoskeletal system, affecting various vital physiological functions.

- Circulatory and Respiratory Compromise: Slouching or excessive rounding of the upper back compresses the chest cavity, thereby reducing lung capacity and the volume of air that can be inhaled with each breath.3 This postural distortion can also strain blood vessels in the neck, potentially affecting blood pressure, and lead to decreased overall circulation, which may manifest as varicose veins or slower wound healing.3

- Digestive Issues: The compression of the stomach and abdomen resulting from poor posture places undue strain on the digestive tract. This can lead to sluggish digestion and, over time, contribute to nutritional issues.5

- Headaches and Jaw Pain: Increased shoulder tension, a direct consequence of poor posture, is a common precursor to headaches.5 Specifically, forward head posture is a significant contributor to cervicogenic headaches and migraines. Moreover, it can alter jaw alignment, potentially leading to Temporomandibular Joint (TMJ) disorder, characterized by pain and dysfunction in the jaw joint.5

- Nerve Compression and Systemic Dysfunction: Spinal misalignment, a hallmark of poor posture, can result in pinched nerves and nerve compression, radiating pain throughout the body.3 Forward head posture, for instance, places nerves and veins in the anterior neck at risk of herniation, compression, and injury. This can critically affect the autonomic nervous system, potentially leading to dysfunction in vital functions such as heart rate, digestion, and breathing.7

- Long-Term Degeneration: Chronic poor posture can lead to insidious and progressive structural damage. This includes arthritic degeneration of the cervical spine, the loss or even reversal of its natural lordotic curve, and generalized joint degeneration throughout the body.7 The concept of “ligament creep,” a slow stretching of ligaments due to sustained poor posture, and its progression to “arthritic degeneration” highlights that the damage is often not acute but a gradual, cumulative structural degradation over time. This makes early and consistent intervention paramount to prevent irreversible conditions. Ignoring ergonomic issues can lead to a more complex and expensive array of health problems, making early intervention a critical preventative strategy for overall health, not just musculoskeletal health.

2.3. The Mental Health Connection

The ramifications of working posture extend beyond physical discomfort, significantly influencing mental well-being. Working postures, particularly those that induce musculoskeletal pain or are maintained improperly for extended durations, are demonstrably associated with increased rates of depression among workers.12 The presence of chronic pain, a frequent outcome of poor posture, can lead to substantial psychosocial impacts. These include symptoms of depression and anxiety, feelings of loneliness, and frustration, all of which can exacerbate existing psychological issues and impede social interactions.10

Furthermore, suboptimal ergonomic conditions, when combined with the inherent physical and psychological demands of professional roles, can jeopardize overall employee well-being. This contributes to phenomena such as burnout, job dissatisfaction, and increased absenteeism.13 Conversely, adopting and maintaining good posture has been shown to have a positive impact on an individual’s mood and self-confidence.5 This indicates that ergonomic considerations are not merely about physical comfort but are a crucial component of holistic employee well-being and mental health support.

Table 1: Common Posture Mistakes and Their Health Impacts

| Posture Mistake | Key Physical Impacts | Key Mental/Systemic Impacts |

| Slumped Sitting | Back pain (LBP, herniated discs, sciatica), Muscle imbalances/weakness, Stiffness, Reduced blood flow, Potbelly, Bent knees when standing | Fatigue, Stress, Sluggish digestion, Reduced circulation |

| Forward Head Posture (“Tech Neck”) | Neck pain (cervical strain, stiffness, degeneration), Headaches/Migraines, Muscle tension (neck/shoulders), Mid-back/chest discomfort, Cervical radiculopathy, TMJ Disorder, Arthritic degeneration of cervical spine | Brain fog, Dizziness, Cognitive problems, Autonomic nervous system dysfunction, Anxiety attacks |

| Rounded Shoulders | Upper back/neck/shoulder stiffness, Chronic pain, Reduced shoulder mobility/flexibility, Jaw pain, Muscle imbalances (tight chest, weak upper back) | Reduced lung capacity, Psychosocial health issues (depression, anxiety), Poor balance |

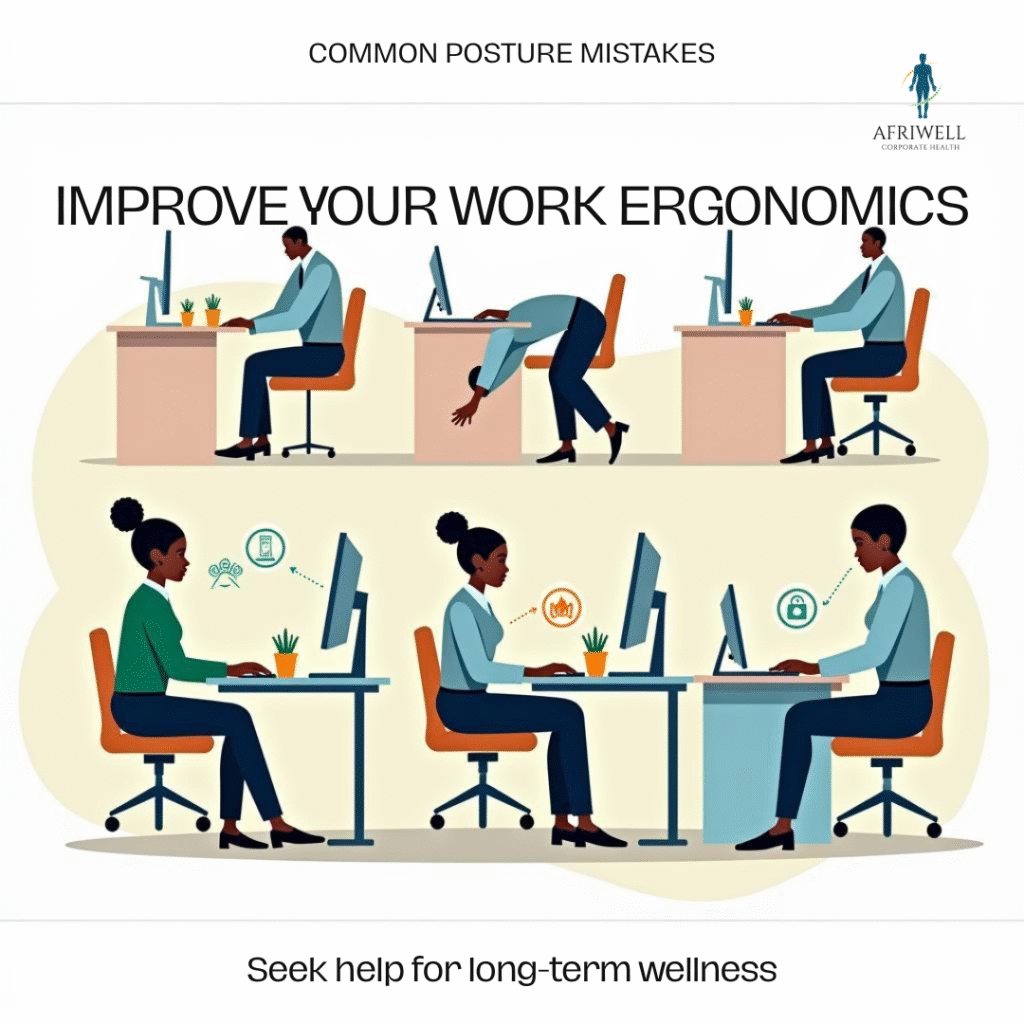

3. Common Posture Mistakes You’re Probably Making at Work

Understanding the specific ways in which posture deviates from optimal alignment is crucial for effective intervention. Modern work habits often perpetuate a cycle of specific postural errors, each with distinct and compounding negative effects.

3.1. Slumped Sitting (Sedentary Slouch)

Slouching or leaning forward is a ubiquitous posture in sedentary work environments. This position exerts compressive forces on the intervertebral discs, the soft, gelatinous cushions situated between the vertebrae that function as shock absorbers for the spine.3 Over time, this sustained compression can lead to or exacerbate disc degeneration, herniation, and nerve compression, culminating in chronic back pain and associated symptoms such as sciatica.3

Beyond direct spinal impact, slumped sitting creates significant muscular imbalances. It causes the muscles in the back and shoulders to become overstretched and weakened, while the muscles in the chest shorten and tighten.14 This imbalance contributes to muscle weakness, stiffness, and reduced blood flow to the affected musculature and tissues of the back.14 Furthermore, this posture can contribute to a “potbelly” appearance and a tendency for knees to be bent even when standing.11 It interferes with the body’s natural postural mechanisms, leading to an over-reliance on “phasic” muscle fibers, which fatigue quickly, rather than the more enduring “static” fibers designed for sustained postural support.11 This illustrates a critical behavioral-structural feedback loop: poor sitting habits lead to muscular and structural changes that, in turn, reinforce the poor posture, making correction increasingly difficult over time.

3.2. Forward Head Posture (“Tech Neck”)

Forward head posture, colloquially known as “tech neck,” is an increasingly prevalent condition directly attributable to prolonged periods spent looking down at screens, whether on laptops, tablets, or smartphones.5 The biomechanical strain imposed by this posture is substantial: for every inch that the head protrudes forward, the force exerted on the cervical spine increases by an additional 10-12 pounds.9 This significant increase in load leads to chronic strain on the neck and upper back.

A critical consequence of this sustained strain is the slow stretching of posterior neck ligaments, a phenomenon termed “ligament creep”.9 This gradual deformation can eventually lead to arthritic degeneration of the cervical spine and the loss or even reversal of its natural lordotic curve.9 The symptoms associated with forward head posture are varied and debilitating, including chronic neck pain, headaches, muscle tension in the neck and shoulders, discomfort in the mid-back, and even chest pain.8 More severe manifestations can include cervical radiculopathy, cervicogenic headaches, and dizziness.9 The quantifiable impact of forward head posture, particularly the additional force exerted per inch of forward displacement, and the concept of “ligament creep,” reveal that seemingly minor, habitual posture deviations accumulate significant, long-term biomechanical stress, often without immediate pain. This often leads to severe conditions later in life.

3.3. Rounded Shoulders (Upper Crossed Syndrome)

Rounded shoulders, a common postural misalignment, arise from muscle imbalances and uneven weight distribution within the upper body.10 This condition frequently develops from prolonged periods spent in sitting positions without adequate stretching or movement. Such static postures cause the muscles of the chest and the front of the arms to shorten and tighten, while the muscles of the upper back and neck become weakened and lengthened.10 This imbalance pulls the shoulders forward and rounds the upper back.

This posture is particularly prevalent among sedentary employees who regularly perform upper limb motions, such as those engaged in computer work.15 The symptoms associated with rounded shoulders include stiffness and chronic pain in the upper back, neck, and shoulders, accompanied by reduced mobility and flexibility in the shoulder joint, which can significantly hinder the ability to perform daily activities.10 Untreated, rounded shoulders can lead to more severe complications, including reduced lung capacity due to the constriction of the chest cavity, psychosocial health issues such as depression and anxiety stemming from chronic pain, compromised balance, and even jaw pain.10 This further underscores the behavioral-structural feedback loop, where sustained poor habits create physical adaptations that perpetuate the problem, making correction increasingly challenging over time.

4. The Ergonomic Equation: Setting Up Your Workspace for Success

Implementing sound ergonomic principles is fundamental to mitigating the risks associated with poor posture and promoting overall well-being in the workplace. Ergonomics, as an applied science, focuses on designing the job, equipment, and work environment to optimally fit the worker, thereby maximizing productivity while simultaneously reducing fatigue, injury, and discomfort.16

4.1. Foundational Principles of Ergonomic Design

At the core of ergonomic design is the principle of maintaining proper spinal alignment.3 This involves ensuring that the body’s major joints—shoulders, hips, knees, and ankles—are stacked in a vertical column. Activating the core muscles is crucial for providing stability and support to the spine, while the shoulders should remain relaxed and slightly pulled back, rather than hunched forward.3 The head and neck must be aligned in a neutral position, with the ears positioned directly over the shoulders and the chin parallel to the ground.3 The overarching goal of these principles is to preserve the natural curves of the spine and distribute body weight evenly, thereby minimizing undue stress on joints and surrounding tissues.3 The consistent emphasis on adjustability across all workstation components and the acknowledgment that individual ergonomic requirements vary underscores that a “one-size-fits-all” ergonomic solution is inherently ineffective. True ergonomic success lies in personalized setups that accommodate diverse body types and task requirements.

4.2. Optimizing Your Workstation Components

The effectiveness of an ergonomic setup hinges on the meticulous configuration of its individual components to support natural posture and reduce strain.

- Monitor Placement: The computer monitor should be positioned directly in front of the user, centered, and at an arm’s length distance, typically around 20 inches from the eyes.17 For optimal neck and head alignment, the top of the monitor should be at or slightly below eye level, or within the top third of the screen for larger displays.3 A slight backward tilt of 10-20 degrees can help maintain the viewing distance, while users with bifocals may benefit from lowering the monitor and tilting it back 30-45 degrees.19 When using multiple monitors, the primary screen should be directly in front, with adequate space for secondary displays. For laptops, a docking station is recommended to allow for proper external monitor positioning.17 To minimize eye strain and glare, monitors should have a matte finish, and their placement should avoid direct exposure to bright windows.16

- Chair Configuration: An ergonomic chair is a cornerstone of a healthy workstation. It should be easily and pneumatically adjustable, allowing for height changes while seated.17 The seat height should permit the feet to rest flat on the floor or a footrest, with knees at or slightly below hip level, maintaining a 90-degree or greater angle at both hips and knees.3 The seat pan itself should be comfortable, contoured, at least one inch wider than the user’s hips and thighs, and feature a “waterfall” front edge to prevent pressure behind the knees.17 The backrest must provide comfortable and adjustable lumbar support, capable of moving up, down, forward, and backward, and be sufficiently large to support the mid and upper back.16 If armrests are utilized, they should be broad, contoured, cushioned, and adjustable in both height and width to allow the shoulders to remain relaxed and the elbows to hang naturally at the sides.16 For stability and mobility, a sturdy five-legged base with freely gliding casters and a 360-degree swivel is recommended.17

- Desk, Keyboard, and Mouse: The desk should offer sufficient depth to accommodate the monitor at the correct viewing distance and provide ample work surface for all necessary items, including the keyboard, mouse, and documents.17 The keyboard height should be approximately at elbow level, allowing the forearms to be parallel to the floor and the wrists and hands to maintain a straight, neutral line.14 Adjustable height desks, such as sit-stand models, are highly beneficial for promoting dynamic posture.17 The mouse should be positioned as close to the keyboard as possible to minimize excessive reaching and reduce shoulder strain. Cordless mice or those with detachable number keypads can further reduce reach requirements.16 Wrist rests, when used, should match the keyboard’s front edge in width, height, slope, and contour, ideally being soft but firm (gel materials are recommended) and at least 1.5 inches deep. It is crucial to remember that wrist rests are intended for resting, not for active keying.17 Finally, the workspace must provide sufficient leg and knee clearance under the desk, with minimum depths of 17.6 inches for knees and 24 inches for feet, and a minimum width of 20.8 inches for knees.16

The consistent emphasis on adjustability across all workstation components and the acknowledgment that individual ergonomic requirements vary underscores that a “one-size-fits-all” ergonomic solution is inherently ineffective. True ergonomic success lies in personalized setups that accommodate diverse body types and task requirements. Furthermore, the varying evidence regarding the effectiveness of specific interventions, such as lumbar supports, indicates that while the overall principles of ergonomics are strongly supported, individual products may have nuanced efficacy. This suggests that careful consideration and potentially individualized assessment are necessary for optimal results.

Table 2: Ergonomic Workstation Setup Checklist

| Component | Key Guideline |

| Monitor | Top of screen at or slightly below eye level (or top 1/3 for large displays); Arm’s length distance (20-28 inches); Tilted slightly back (10-20 degrees); Centered in front; Matte finish to reduce glare; Avoid facing windows. |

| Chair | Easily adjustable height (feet flat on floor/footrest, knees at 90+ degrees); Lumbar support (adjustable); Contoured seat with “waterfall” front; Breathable, firm material; Armrests (if used) at elbow height, adjustable; 5-pedestal base with casters, swivels 360 degrees. |

| Desk | Sufficient depth for monitor distance; Large enough work surface for all items; Keyboard at elbow height; Rounded or sloping front edges; Ample leg and knee clearance underneath. |

| Keyboard/Mouse | Positioned close together; Neutral wrist position (straight line); Wrist rest for resting only, not active typing; Choose appropriate size/type for hand. |

| Feet/Legs | Feet flat on floor or footrest; Knees at 90 degrees or greater; Legs uncrossed; Vary seated posture periodically. |

| Breaks | Incorporate regular movement breaks (every 30-60 minutes); Perform stretching exercises; Look away from screen (20-20-20 rule for mobile devices). |

5. Beyond the Setup: Habits for Healthy Posture

While an ergonomically optimized workstation provides the foundational support for good posture, its benefits are maximized when complemented by conscious habits and a holistic approach to personal well-being. The human body is not designed for prolonged static positions, whether seated or standing.14 Sustained immobility can lead to muscle tightness, reduced circulation, and the onset of discomfort and pain.14 This highlights that effective ergonomics is not merely about a perfect initial workstation configuration but about continuous behavioral adaptation and dynamic interaction with the work environment.

5.1. The Imperative of Movement and Breaks

Regular movement throughout the workday is crucial for preventing stiffness and muscle fatigue. Simple, yet effective, practices include setting a timer to prompt getting up and moving every hour, or even every 30 minutes.3 Incorporating short walks or performing simple desk exercises can significantly promote circulation and relieve tension in the spine and surrounding muscles.3 For individuals extensively using mobile devices, specific guidelines are recommended: limiting overall usage time, adhering to the “20-20-20 rule” (looking away every 20 minutes at an object approximately 20 feet away for a full 20 seconds), and ensuring adequate rest periods to reduce musculoskeletal complaints.1 These dynamic habits are as important as static setup guidelines, as the body requires continuous movement to maintain health and prevent the adverse effects of prolonged immobility.

5.2. Mindful Posture Techniques and Body Awareness

Beyond physical adjustments, a conscious awareness of one’s posture is paramount. This involves actively aligning the body’s major joints—shoulders, hips, knees, and ankles—in a stacked position.3 Engaging the core muscles provides essential stability and support for the spine, while maintaining relaxed shoulders, slightly pulled back, helps open the chest.3 Crucially, the head and neck should be aligned with the ears over the shoulders and the chin parallel to the ground, avoiding any forward jutting or tilting.3

Cultivating body awareness means listening to its signals; if muscle tension or fatigue is felt, it is important to shift to a different position.11 Varying seated posture periodically is also highly beneficial.16 For tasks that necessitate standing, lifting, or awkward positions, the aim should always be to maintain as neutral a posture as possible. If awkward postures are unavoidable, implementing task rotation is essential to prevent maintaining these stressful positions throughout an entire shift.16

5.3. General Lifestyle Factors Supporting Good Posture

Poor posture is not solely a consequence of workstation setup; it can be significantly exacerbated by broader lifestyle factors. These include weak muscles, general fatigue, the habit of carrying heavy bags (particularly over one shoulder), and carrying excess body weight.5 A comprehensive approach to preventing musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) therefore extends to individual actions beyond the workplace. Regular exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, and effective stress management are all factors that can substantially reduce the risk of MSDs.21 Incorporating consistent stretching routines, whether as part of a pre- or post-work regimen or through intraoperative “micro-breaks,” has been shown to reduce pain and enhance overall physical well-being.1 The inclusion of these factors demonstrates that workplace posture is intrinsically linked to broader personal health and fitness. This expands the scope of “workplace ergonomics” beyond the immediate desk to encompass the employee’s overall physical condition and lifestyle, suggesting that a truly comprehensive approach to reducing MSDs and improving posture requires addressing general wellness.

6. The Business Case for Ergonomics: Productivity, Well-being, and Economic Benefits

The implementation of ergonomic principles within the workplace is not merely a matter of employee comfort; it represents a strategic investment with profound implications for organizational productivity, employee well-being, and overall economic performance.

6.1. Impact on Productivity and Performance

Poor office ergonomics significantly diminishes employee effectiveness and cognitive function. Research indicates a measurable decline in concentration, problem-solving abilities, and memory function among workers in poorly designed environments.23 The discomfort arising from suboptimal positioning activates physiological stress responses, leading to elevated cortisol levels that further impair optimal cognitive performance.23 This cascade of negative effects directly translates to lower quality work output, increased error rates, and diminished creative thinking—all critical components of modern workplace productivity.23 A notable study specifically found that poor posture was associated with a decrease in productivity of up to 66% in office workers.24 Conversely, organizations that have implemented ergonomic interventions have consistently reported significant improvements in productivity levels.25

6.2. Enhanced Employee Well-being and Morale

Favorable ergonomic conditions play a crucial role in enhancing job satisfaction, which in turn positively influences both mental health and overall job performance.13 Ergonomic interventions are instrumental in reducing stress, fatigue, and discomfort, leading to a more content, motivated, and engaged workforce.25 This translates directly into tangible benefits such as reduced absenteeism and improved psychological safety within the workplace, both of which are critical for optimal team performance and collaboration.13 When employers demonstrate attention to ergonomics, employees feel valued, fostering a more positive safety culture and higher morale across the organization.26

6.3. Quantifying the Economic Burden of MSDs

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) represent a substantial economic burden, standing as the leading cause of pain, suffering, and disability in American workplaces.27 They account for over 1 million workplace injuries annually and constitute one-third of all workers’ compensation costs.27 The estimated costs associated with work-related MSDs in the United States range from a staggering $13 billion to $54 billion annually.28

The direct costs of an MSD-related injury can range from $15,000 to $85,000 per case, with workers’ compensation medical costs alone typically falling between $30,000 and $80,000 per case.28 However, these direct costs are often dwarfed by indirect costs, which can double or even triple the total expenditure. For a single work-related strain, indirect costs, encompassing lost productivity, retraining, and personnel reallocation, are estimated at $35,225, compared to direct costs of $32,023.27

Absenteeism due to injury results in an average 36.6% drop in productivity, costing businesses approximately $3,600 per hourly worker each year.28 The financial impact extends to replacement costs, with the average cost to replace an absent worker estimated at $4,700, and some employers reporting figures three to four times the position’s salary.28 A particularly significant, yet often hidden, cost is “presenteeism”—the phenomenon of employees working while experiencing pain or limited function.28 This can reduce productivity by 20-40% per affected worker, with estimated costs ranging from $3,000 to $10,000 per year in lost productivity per employee suffering from chronic pain due to an MSD.28 The explicit identification and quantification of “presenteeism” as a significant cost factor reveals a hidden economic burden that often goes unmeasured by organizations. This implies that the true financial impact of poor ergonomics is substantially higher than what is reflected in direct costs like workers’ compensation claims or absenteeism.

Globally, approximately 1.71 billion people live with musculoskeletal conditions, making them the highest contributor to years lived with disability (YLDs) worldwide.31 The societal impact of early retirement stemming from MSDs, encompassing both direct healthcare costs and indirect costs such as work absenteeism and productivity loss, is enormous.31 The significant under-reporting of MSDs, estimated to be between 53% and 73% in France, combined with their status as a leading cause of disability globally, suggests that official statistics severely underestimate the true scale of the problem.31 This implies that the societal and economic burden of MSDs is far more profound and pervasive than commonly perceived, making it a critical public health issue that extends beyond individual company concerns.

Table 3: Benefits of Ergonomic Interventions for Organizations

| Benefit Category | Specific Outcomes/Metrics |

| Productivity | Increased concentration, problem-solving, memory; Higher quality work output; Reduced error rates; Avoided decrease in productivity (up to 66% in office workers). |

| Employee Well-being & Morale | Enhanced job satisfaction; Improved mental health; Reduced stress, fatigue, and discomfort; Increased motivation and engagement; Reduced burnout; Improved psychological safety; Employees feel valued. |

| Cost Savings (Direct) | Reduced workers’ compensation claims (e.g., $20 billion annually in US); Lower medical costs per case (e.g., $30,000-$80,000). |

| Cost Savings (Indirect/Hidden) | Reduced absenteeism (e.g., 36.6% productivity drop avoided, $3,600/worker/year saved); Reduced presenteeism (e.g., 20-40% productivity reduction avoided, $3,000-$10,000/worker/year saved); Lower employee turnover and replacement costs. |

| Safety Culture | Fewer injuries; Improved workforce well-being; Better safety culture; Outperformance of competitors (companies with integrated health/safety culture outperformed by up to 325%). |

7. Implementing Ergonomic Solutions: Overcoming Challenges

The successful integration of ergonomic solutions into the workplace requires a strategic and comprehensive approach, acknowledging both the benefits and the inherent challenges.

7.1. The Importance of a Strategic Approach

Implementing a well-designed ergonomic process has proven effective in reducing the risk of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) across a wide array of industries.34 A comprehensive ergonomics program yields substantial benefits, including a reduction in injuries and associated costs, lower employee turnover and absenteeism rates, improved product quality, and a notable increase in overall productivity.27 It is clear that posture corrections are fundamental for reducing health risks in all aspects of life, underscoring the imperative for employers to actively design workspaces that promote ergonomic principles for the mutual betterment of both the organization and its employees.25

7.2. Key Challenges in Implementation

Despite the compelling advantages, organizations often encounter several challenges when implementing ergonomic solutions:

- Employee Engagement and Buy-In: A primary hurdle is overcoming employee skepticism and ensuring active participation.35 Employees may initially perceive ergonomics programs as merely another set of policies imposed by management, rather than a genuine effort to improve their working conditions.35

- Cost and Resource Allocation: The initial investment required for ergonomic equipment, training, or program development can be perceived as substantial, potentially deterring organizations despite the proven long-term savings.26

- Identifying and Assessing Risks: Accurately identifying ergonomic risk factors—such as repetitive motion, static posture, forceful exertion, and awkward positions—and assessing their magnitude, frequency, and duration requires specific knowledge, tools, and systematic processes.4

- Training and Education: Ensuring that the workforce is adequately aware of ergonomic principles, understands their benefits, and recognizes the importance of reporting early symptoms of MSDs necessitates continuous and effective training programs.34

- Ongoing Evaluation and Improvement: Maintaining the effectiveness of an ergonomics program requires periodic assessment and a commitment to continuous improvement, which can be challenging to sustain over time.34

7.3. Strategies for Successful Program Implementation

Overcoming these challenges necessitates a multi-faceted and integrated approach:

- Management Commitment and Leadership: Strong leadership is paramount. Management must clearly define goals, assign responsibilities, and communicate effectively across all organizational levels.34 Leaders should actively support ergonomic initiatives and consistently model safe behaviors, thereby cultivating a top-down culture that unequivocally prioritizes employee well-being.26 This consistent emphasis on employee engagement, management commitment, and comprehensive training demonstrates that implementing ergonomics is not merely a technical adjustment but a complex organizational and cultural change initiative. Success hinges on human factors and leadership, not just equipment.

- Worker Involvement (Participatory Ergonomics): Directly involving workers in worksite assessments, the development of solutions, and their implementation is the essence of a successful ergonomic process.34 Employees, being on the front lines, are uniquely positioned to identify hazards, offer practical suggestions for risk reduction, and evaluate the effectiveness of implemented changes.26

- Comprehensive Training and Education: Educational initiatives should be robust and ongoing, informing staff about MSD risk factors, fundamental ergonomic principles, and practical application to their individual workstations.22 Personalizing ergonomic training to individual workstations and health needs can significantly enhance its impact.26

- Risk Assessment and Control: Organizations must conduct thorough risk assessments for musculoskeletal injuries, meticulously identifying the magnitude, frequency, and duration of exposure to risk factors.36 Control measures should follow a hierarchy: prioritizing the elimination of risk factors (e.g., through mechanical aids or task redesign), followed by risk reduction (e.g., modifying equipment, implementing task rotation, or establishing safe work procedures), with personal protective equipment (PPE) considered only as a last resort.36

- Continuous Improvement and Evaluation: Establishing clear procedures for periodically assessing the effectiveness of the ergonomic process is critical. This ensures that program goals are met and implemented solutions remain successful and relevant over time.34

- Leveraging External Guidelines: Organizations can benefit significantly from referencing international guidelines, such as those jointly prepared by the International Ergonomics Association (IEA) and the International Labour Organization (ILO).37 These documents provide a robust technical basis for developing and standardizing workplace good practices. The existence of these joint IEA/ILO guidelines and the broader call for “system-wide” strategies suggest that addressing MSDs through ergonomics is evolving beyond company-specific best practices to a global public health and labor standard issue. This implies a growing need for standardized approaches and policy support, elevating ergonomics from an optional corporate wellness initiative to a fundamental aspect of occupational health and safety, potentially subject to international standards and regulations.

8. Conclusion: Your Path to a Pain-Free, Productive Workday

8.1. Recapitulation of Key Takeaways

The pervasive nature of poor posture and inadequate ergonomics in modern workplaces, driven by sedentary occupations and the ubiquitous use of digital devices, has led to a silent epidemic of musculoskeletal disorders. The consequences of these postural deviations extend far beyond localized physical pain, impacting a wide array of physiological functions, including circulation, digestion, and respiration, and significantly influencing mental well-being, contributing to conditions such as depression, anxiety, and reduced cognitive function. Common posture mistakes, such as slumped sitting, forward head posture (often termed “tech neck”), and rounded shoulders, contribute to cumulative structural damage that often progresses insidiously over time, making early intervention critical.

Effective solutions to this widespread challenge necessitate a dual approach: optimizing workstation ergonomics through personalized setup and fostering dynamic habits that prioritize regular movement, strategic breaks, and mindful posture. Critically, there is a compelling business case for investing in ergonomics. Such interventions yield significant returns through enhanced productivity, improved employee well-being, reduced absenteeism, and substantial cost savings derived from the prevention and mitigation of musculoskeletal disorders.

8.2. The Interconnectedness of Posture, Ergonomics, and Overall Well-being

The evidence presented underscores that good posture is not merely an aesthetic consideration but a foundational element of overall health, productivity, and quality of life. The human body is an interconnected system, where compromises in one area, such as spinal alignment, can cascade into broader physiological dysfunctions and even affect mental states. Therefore, ergonomic interventions should be viewed as strategic investments in human capital, yielding benefits that extend far beyond the immediate reduction of physical discomfort, positively impacting both individuals and the organizations they serve.

8.3. Call to Action for Individuals and Organizations

Addressing the silent epidemic of poor workplace posture requires concerted effort from both individuals and organizations.

- For Individuals: It is imperative to take personal responsibility for one’s posture. This involves actively implementing ergonomic adjustments to personal workspaces, consciously incorporating regular movement and breaks throughout the workday, and prioritizing holistic fitness, encompassing consistent exercise, maintaining a healthy weight, and effective stress management. These personal commitments are vital for building resilience against the demands of modern work.

- For Organizations: Prioritizing and investing in comprehensive ergonomic programs is a strategic imperative. This requires strong management commitment, active employee involvement through participatory ergonomics, continuous training and education on best practices, and robust systems for risk assessment and control. Organizations must recognize ergonomics not just as a compliance measure but as a critical investment in their human capital, fostering a healthier, more productive, and resilient workforce that can thrive in the evolving landscape of work.

References:

- 1 Al-Khateeb, A. A., & Al-Zoubi, A. A. (2022). Prevalence of musculoskeletal discomfort among university students using mobile devices during the COVID-19 pandemic.

PMC, 9556879. - 2 Al-Zoubi, A. A., & Al-Khateeb, A. A. (2025). Low back pain and sitting time, posture and behavior in office workers: A scoping review.

Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. - 12 Cho, Y. S., & Kim, J. H. (2022). Association between working posture and depression in workers.

PMC, 8954532. - 5 Brown Health. (n.d.). Posture and how it affects your health.

Brown Health. - 6 Al-Zoubi, A. A., & Al-Khateeb, A. A. (2024). Effectiveness of ergonomic interventions for posture academic studies.

MDPI, 14(9), 3034. - 38 van Dieën, J. H., & van der Beek, A. J. (2009). Effectiveness of an ergonomic intervention on work-related posture and low back pain in video display terminal operators: a 3-year cross-over trial.

ResearchGate, 256461176. - 4 Hashim, N. H., & Nasir, N. M. (2017). A study on the ergonomic assessment in the workplace.

ResearchGate, 319851863. - 39 Højberg, H., & Rasmussen, C. D. N. (2015). Identifying knowledge gaps between practice and research for implementation components of sustainable interventions to improve the working environment: A rapid review.

Bohrium, 813089974441213954-3898. - 3 Spine Health. (n.d.). Spine posture workplace ergonomics.

Spine Health. - 14 Connolly, C. (n.d.). 5 common posture mistakes at work.

Dr. Christopher Connolly. - 8 Physio-Pedia. (n.d.). Forward Head Posture.

Physio-Pedia. - 9 Caring Medical. (n.d.). Forward head posture symptoms and complications.

Caring Medical Fort Myers. - 10 Wikipedia. (n.d.). Rounded shoulder posture.

Wikipedia. - 15 Al-Zoubi, A. A., & Al-Khateeb, A. A. (2022). Rounded shoulders posture effects.

MDPI, 12(7), 3333. - 11 Better Health Channel. (n.d.). Posture.

Better Health Victoria. - 7 Integrehab. (n.d.). Addressing the effects of poor posture.

Integrehab. - 17 OSHA. (n.d.). Computer Workstations: Purchasing Guide.

OSHA. - 34 OSHA. (n.d.). Ergonomics.

OSHA. - 20 Cornell University. (n.d.). Ergonomic chair recommendations.

Ergo.human.cornell.edu. - 19 Ergotron. (n.d.). Ergonomic monitor placement guidelines.

Ergotron. - 18 TechPowerUp. (n.d.). So what is the correct position for the monitor.

TechPowerUp Forums. - 23 Gymba Ergonomics. (2025). How does poor office ergonomics affect productivity?

Gymba Ergonomics. - 24 Anthros. (n.d.). 66% Loss In Worker Productivity Due To Poor Posture.

Anthros. - 13 Al-Zoubi, A. A., & Al-Khateeb, A. A. (2024). Poor ergonomics effect on employee well-being studies.

PMC, 12071776. - 25 Al-Zoubi, A. A., & Al-Khateeb, A. A. (2024). The Impact of Ergonomic Interventions on Employee Productivity and Wellbeing.

ResearchGate, 388632646. - 28 WorkCare. (n.d.). Uncovering hidden costs of work-related MSDs.

WorkCare. - 27 NC State University. (n.d.). The Business Case for Implementing an Ergonomics Program.

ErgoCenter.ncsu.edu. - 35 SBN Software. (n.d.). What are the challenges of implementing an ergonomics program?

SBN Software. - 35 SBN Software. (n.d.). Employee Engagement and Buy-In.

SBN Software. - 29 WorkCare. (n.d.). Uncovering Hidden Costs of Work-related MSDs – WorkCare.

WorkCare. - 30 CDC NIOSH. (2014). Work-related musculoskeletal disorders (MSD).

CDC NIOSH. - 32 APHA. (2014). Musculoskeletal disorders as a public health concern.

APHA Policy Briefs. - 31 WHO. (n.d.). Musculoskeletal conditions.

WHO Fact Sheets. - 33 ADT Tools. (n.d.). MSD cause disability industry.

ADT Tools. - 21 Number Analytics. (2025). Impact of biomechanical risk factors.

Number Analytics Blog. - 22 StatPearls. (n.d.). Importance of ergonomic education workforce.

NCBI Bookshelf. - 26 Oregon OSHA. (n.d.). The Advantages of Ergonomics.

Oregon OSHA. - 16 UT Dallas. (n.d.). Workplace health and safety policy ergonomics.

Risk-Safety.UTDallas.edu. - 36 WorkSafeBC. (n.d.). Ergonomics.

WorkSafeBC. - 37 IEA & ILO. (2021). Principles and Guidelines for Human Factors/Ergonomics (HF/E) Design and Management of Work Systems.

IEA.cc. - 40 Qualtrics. (n.d.). Secondary Research: Definition, Methods & Examples.

Qualtrics. - 41 SurveyMonkey. (n.d.). What is secondary research?

SurveyMonkey. - 42 University of Mary Washington. (n.d.). Guidelines for a research paper.

CAS.UMW.edu. - 43 George Washington University. (n.d.). Guide to writing research paper.

WritingProgram.GWU.edu.

Works cited

- The prevalence of bad posture and musculoskeletal symptoms originating from the use of gadgets as an impact of the work from home program of the university community, accessed August 6, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9556879/

- Low back pain and sitting time, posture and behavior in office workers: A scoping review, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/390036012_Low_back_pain_and_sitting_time_posture_and_behavior_in_office_workers_A_scoping_review

- Spine Health: Posture and Workplace Ergonomics, accessed August 6, 2025, https://spinehealth.org/article/spine-posture-workplace-ergonomics/

- (PDF) A study on the ergonomic assessment in the workplace – ResearchGate, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319851863_A_study_on_the_ergonomic_assessment_in_the_workplace

- Posture and How It Affects Your Health | Brown University Health, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.brownhealth.org/be-well/posture-and-how-it-affects-your-health

- Efficacy of Ergonomic Interventions on Work-Related Musculoskeletal Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis – MDPI, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/14/9/3034

- Addressing the Effects of Poor Posture | Integrated Rehabilitation Services, accessed August 6, 2025, https://integrehab.com/blog/back-pain/effects-poor-posture/

- www.physio-pedia.com, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.physio-pedia.com/Forward_Head_Posture

- Forward head posture symptoms and complications – Hauser Neck Center Fort Myers -, accessed August 6, 2025, https://caringmedical.com/prolotherapy-news/forward-head-posture-symptoms-and-complications-caring-medical-fort-myers/

- Rounded shoulder posture – Wikipedia, accessed August 6, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rounded_shoulder_posture

- Posture | Better Health Channel, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.betterhealth.vic.gov.au/health/conditionsandtreatments/posture

- The Association between Working Posture and Workers’ Depression – PMC, accessed August 6, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8954532/

- Effects of Psychosocial and Ergonomic Risk Perceptions in the Hospital Environment on Employee Health, Job Performance, and Absenteeism – PubMed Central, accessed August 6, 2025, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12071776/

- 5 Common Posture Mistakes at Work That Are Ruining Your Back Health, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.drchristopherconnolly.com/5-common-posture-mistakes-at-work/

- Effect of Rounded and Hunched Shoulder Postures on Myotonometric Measurements of Upper Body Muscles in Sedentary Workers – MDPI, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/12/7/3333

- Ergonomics – Institutional Risk & Safety | The University of Texas at Dallas, accessed August 6, 2025, https://risk-safety.utdallas.edu/occupational-health-and-safety/ergonomics/

- eTools : Computer Workstations – Checklists – Purchasing Guide | Occupational Safety and Health Administration, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.osha.gov/etools/computer-workstations/checklists/purchasing-guide

- So what IS the correct position for the monitor? | TechPowerUp Forums, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.techpowerup.com/forums/threads/so-what-is-the-correct-position-for-the-monitor.317826/

- The Ergonomic Equation – Ergotron, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.ergotron.com/en-us/ergonomics/ergonomic-equation

- Choosing an ergonomic chair – CUergo, accessed August 6, 2025, https://ergo.human.cornell.edu/AHTutorials/chairch.html

- The Impact of Biomechanical Risk Factors on Musculoskeletal Health, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.numberanalytics.com/blog/impact-of-biomechanical-risk-factors

- Ergonomics – StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK580551/

- How does poor office ergonomics affect productivity? – Gymba, accessed August 6, 2025, https://gymba-ergonomics.com/2025/05/09/how-does-poor-office-ergonomics-affect-productivity/

- www.anthros.com, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.anthros.com/blog-pain/66-loss-in-worker-productivity-due-to-poor-posture#:~:text=One%20study%20found%20that%20poor,to%2066%25%20in%20office%20workers.

- The Impact of Ergonomic Interventions on Employee Productivity and Wellbeing, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388632646_The_Impact_of_Ergonomic_Interventions_on_Employee_Productivity_and_Wellbeing

- The Advantages of Ergonomics – Oregon OSHA, accessed August 6, 2025, https://osha.oregon.gov/OSHAPubs/ergo/ergoadvantages.pdf

- costs of MSDs – The Ergonomics Center, accessed August 6, 2025, https://ergocenter.ncsu.edu/ergohowl_q2_2021/

- Uncovering Hidden Costs of Work-related MSDs – WorkCare, accessed August 6, 2025, https://workcare.com/resources/blog/uncovering-hidden-costs-of-work-related-msds/

- workcare.com, accessed August 6, 2025, https://workcare.com/resources/blog/uncovering-hidden-costs-of-work-related-msds/#:~:text=The%20National%20Institute%20for%20Occupational,billion%20to%20%2454%20billion%20annually.

- National Occupational Research Agenda for Musculoskeletal Disorders | NIOSH – CDC, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2001-117/default.html

- Musculoskeletal health – World Health Organization (WHO), accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/musculoskeletal-conditions

- Musculoskeletal Disorders as a Public Health Concern, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.apha.org/policy-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-briefs/policy-database/2014/07/08/14/21/musculoskeletal-disorders-as-a-public-health-concern

- MSDs, the leading cause of disability in the manufacturing industry – ADT Tools, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.adt-tools.com/en/news/msd_cause_disability_industry/

- Ergonomics – Overview | Occupational Safety and Health Administration, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.osha.gov/ergonomics

- sbnsoftware.com, accessed August 6, 2025, https://sbnsoftware.com/blog/what-are-the-challenges-of-implementing-an-ergonomics-program/

- Ergonomics – WorkSafeBC, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.worksafebc.com/en/health-safety/hazards-exposures/ergonomics

- Principles and Guidelines for Human Factors/Ergonomics (HF/E) Design and Management of Work Systems, accessed August 6, 2025, https://iea.cc/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Principles-and-Guidelines_June2021.pdf

- Effectiveness of an ergonomic intervention on work-related posture and low back pain in video display terminal operators: a 3 year cross-over trial. – ResearchGate, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/256461176_Effectiveness_of_an_ergonomic_intervention_on_work-related_posture_and_low_back_pain_in_video_display_terminal_operators_a_3_year_cross-over_trial

- Identifying knowledge gaps between practice and research for implementation components of sustainable interventions to improve the working environment – A rapid review – Bohrium, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.bohrium.com/paper-details/identifying-knowledge-gaps-between-practice-and-research-for-implementation-components-of-sustainable-interventions-to-improve-the-working-environment-a-rapid-review/813089974441213954-3898

- www.qualtrics.com, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.qualtrics.com/experience-management/research/secondary-research/#:~:text=Secondary%20research%2C%20also%20known%20as,bodies%2C%20and%20the%20internet).

- What Is Secondary Research? | SurveyMonkey, accessed August 6, 2025, https://www.surveymonkey.com/mp/what-is-secondary-research/

- Guidelines for a Research Paper – History and American Studies, accessed August 6, 2025, https://cas.umw.edu/historyamericanstudies/history/history-department-resources/final-papers/guidelines-for-a-research-paper/

- A Guide to Writing a Research Paper | University Writing Program | Columbian College of Arts & Sciences, accessed August 6, 2025, https://writingprogram.gwu.edu/guide-writing-research-paper

Leave Your Comment